Photo exhibition “Fake Truth” by Alison Jackson in Vienna’s Westlicht museum

One of the photos by Alison Jackson that can be seen in Vienna © Alison Jackson

Yasemin Elci

When Princess Diana died in 1997, Alison Jackson got a gun and started shooting at the image of Diana to see if she could erase it from her memory. She couldn’t, and neither could the public.

Newspapers elaborated on Diana’s death describing her body parts in detail, which intrigued Jackson. Testing the extent of this “mass voyeurism”, Jackson used a look-a-like to create fake images of Diana to (successfully) provoke a public reaction.

A British contemporary artist with a BAFTA award, Jackson works at the fine line between real and imaginary, questioning the reliability of our perception. “Fake news” is Jackson’s artistic language.

She uses actors to produce images that show private moments of celebrities that look more real than real life. Her staged photographs investigate obsession with celebrity, our weak sense of truth and our firm belief in our own judgements.

Celebrities’ secrets isn’t what Jackson exposes. What we are looking at is our own fixation on these (social) media icons.

Craving for a glimpse of the lives of others – real or fake – we check our phones even on the loo. In “Fake Truth” at Vienna’s WestLicht photography museum, Queen Elizabeth in fact greets us from what may purport to be a Buckingham Palace toilet.

Lady Di gives us the finger, George W. Bush is challenged by a smart cube, Kim Kardashian is giving birth on live TV, Donald Trump has a moment with Miss Mexico, and Michael Jackson offers a pacifier to a baby.

But celebrities’ secrets isn’t what Jackson (the photographer, not the disco star) exposes. What we are looking at in her work is our own fixation on these (social) media icons. She shows how we are seduced, provoked and manipulated. Believe it or not, the camera lies to us.

In fact, American writer Susan Sontag considered the camera as a weapon. “To photograph people is to violate them, by seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them that they can never have; it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed,” she said in her “On Photography” collection of essays.

The photographer has the ability to both capture and construct reality, and which choice she makes, is not revealed to the observer. It would be easy to blame the blurring division on digitalisation, but photo editing has been used since the invention of the first cameras and early processing techniques. Retouching was a common method for idealisation, satire or rewriting history. Hitler, Lenin, Stalin and Mussolini all used it.

Alison Jackson is not only a photographer or a contemporary artist. Rather, she acts like a social critique, observing idiosyncrasies with a magnifying glass. She has produced TV series, advertisements, books and theater performances, resisting censorship at times.

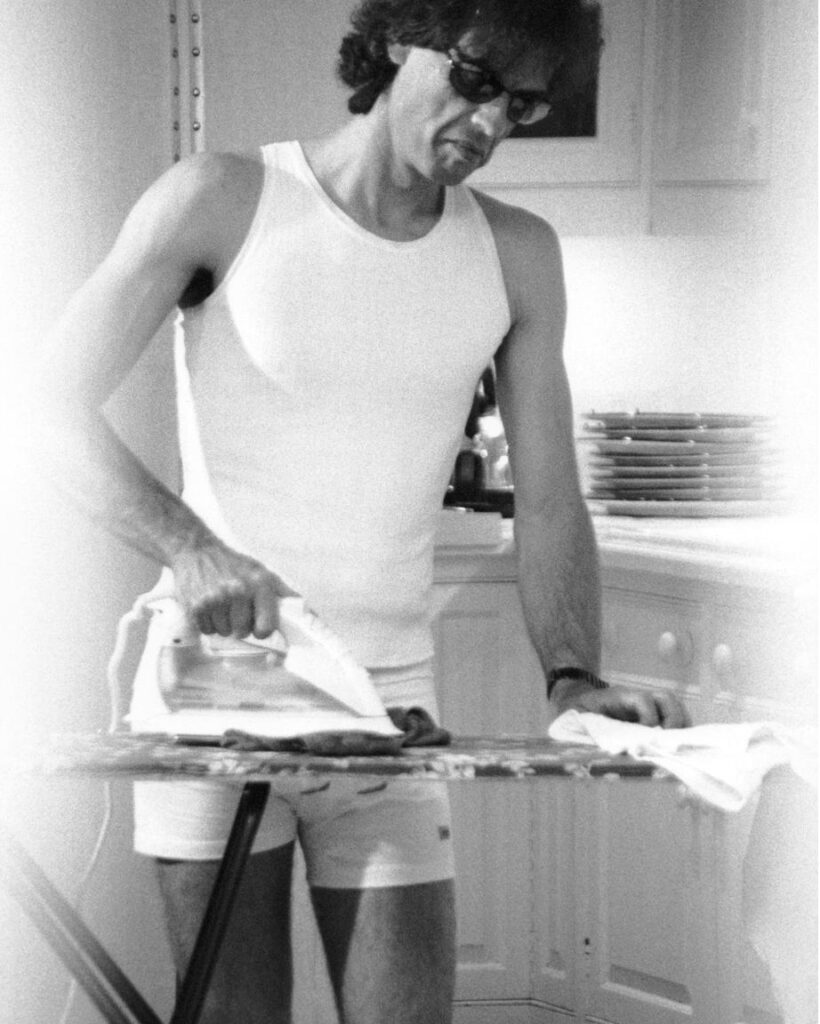

Jagger Ironing © Alison Jackson

Her work has been acquired by prestigious art institutions such as the Royal College of Art (London), SF MOMA (San Francisco), the Musée de la Photographie de Charleroi (Brussels), the International Centre of Photography (New York) and the Centre Pompidou. Her current exhibition at WestLicht is running until January 26, 2020.

Dedicated to exploring “the interrelation between camera technology and the photographic image, between apparatus and print” the museum is not only a reference point for the history of photography, but also home to its finest examples today. As the integrity of Jackson’s work depends on the deceitfulness of the medium, WestLicht now hosts a timeless social experiment.

Jackson’s actors or “nobodies” which turn into “celebrities” are forgotten in the blink of an eye as the visitor shifts his attention to the next photograph.

Weapons of mass manipulation and their immediate impact are displayed simultaneously. Alison Jackson’s powerful exhibition “Fake Truth” demonstrates that voyeurism does not feed from truth, and its after-taste does not fade even when the subject’s authenticity is revealed.